Co-creation cornerstones and challenges

Stakeholders in many national contexts of service governance often do not have experience in co-creation practices and how it may be supported by managers and appropriate governance. “We started from zero with no knowledge of co-creation” is an expression from several CoSIE pilots. We also learned that both the role of individuals and contexts matter and that failing to meet the core conditions will fail the co-creation.

Based on the findings from 9 national contexts we illustrate some major conditions or cornerstones for co-creation (for more, see Roadmap for co-creation on the project webpage):

- Infrastructure: Infrastructure and experimental spaces: Sustaining co-creative spaces require not only decision-makers’ approval, financial support but also specific infrastructure (such as meeting spaces) and building relationships to keep the motivation. For political organizations, to really engage in co-creation requires aligning co-creative experiments to their plans and schedules to free time and resources for experimental efforts and spaces (Holland, Houten, Hungary, Sweden, etc) Formal and genuine support from top decision-makers is also essential yet in a way that do allow flexibility. Yet convincing politicians may be a challenge when short-term effects are prioritised over longer-term gains as often the case with co-creation; given their short-lived positions.

- Multiple stakeholders: Relevant/Multiple stakeholders: all contributing stakeholders need to be identified and enrolled. The organizational and sectorial diversity of public, private and third sector actors is important to assure a rich and multidimensional comparison of ideas, suggestions, and methodologies (examples can be found in Italy, Spain, Hungary, and Estonia). Therefore, the capacity to involve qualified stakeholders, to engage them and to value their work is fundamental. Reaching out needs well thought and adapted strategies, such as personal visits (Estonia), using neutral professionals (Sweden) or enhancing accessibility by digital tools (Spain).

- When co-creation is new it may be hard to engage multiple stakeholders for common goal and sustain their effort. Our pilot’s evidence that having a concrete focus, why to co-create may really help (for example Italian case). Also consistence in sustaining efforts to convince and stakeholders including service professionals (Finland)

- Engaging (marginalized) users: the co-creation process always has to involve the targeted individuals supported by the services. Their point of view, when presented professionally and repeatedly (see Finish or UK case) often serve to convince professionals and managers of the need for co-creation, and is crucial to develop or improve a service or policy in the most adequate way. Yet, finding and reaching out to those individuals, when they are marginalized, perhaps also digitally marginalized as was the case under pandemic, requires some effort. Overcoming lack of trust, previous disappointments and fair of being unjustly exposed have to be overcome (see for example the Polish, UK and Dutch pilots).

- Appropriate use of digital tools: These individuals need different platforms and tools, including digital ones, for reaching out and reporting of their lived experiences for a just co-creation. Community Reporting has served as one of them, focus groups and hackathons are examples of other effective methods.

- Co-creative professionals – changing attitudes and roles: Right approach to their roles in co-creative relationships with beneficiaries and support of front-line managers and service professionals is vital in co-creative design and implementation, yet their contributions may not be taken for granted. Co-design is enabled by modifying the professional-user interface to increase the latter’s active input into at least some aspects of decision making about the service individually provided for them. In Sweden) and the UK, much effort and resource was devoted to training and coaching for front-line of professionals to support such a shift and resulted in a shift in approaches.

- Common ethics and language: To increase the possibilities that the co-creation process is successful the different languages used by the stakeholders need to find a convergence towards a common language, which defines also common objectives, expectations of roles, relationships and methodologies. The convergence may be achieved thanks to a close and repeated conversation among all actors (regular meetings among all stakeholders may contribute in developing a common sense- and decision-making as in Italy, Sweden, and Spain). The failure in creating a convergent language results, instead, in a cacophonous language, where the communication remains a sum of different languages that do not merge into one (in UK the stakeholders did not produce a common way to act due to different approaches, values and priorities). Comparisons between our 9 national contexts show that we might be emphasizing different words to introduce co-creation (see “Co-creation: are we all talking about the same thing?”. Clarifying what co-creation is and how it differs from other more familiar terms is essential for motivating service professionals to engage and learn more.

- Motivated intermediaries: the projects that reckon on the presence of motivated intermediaries were successful in finding and engaging the stakeholders and facilitating sensemaking about the co-creative processes and necessary approaches (for example UK, Italy, Sweden). The intermediary is meant here as a third party, i.e. a mediator or boundary spanner, which every other actor can recognise as facilitator or even guarantor for structured advancement of the innovation or improvement process and for the protection of the data or information shared. The intermediary succeeds in leading the network when each actor has its responsibility and is not disempowered by the intermediary guidance.

- Raising awareness: The benchmarking activities such as through Living Lab, local knowledge exchange (see the Polish pilot) and cross-national workshops have been important for raising awareness about relational services and co-creative approach, for its exploration and dissemination among practitioners, participatory action researchers, decision-makers and beneficiaries.

- System change: For change in the service system, it is especially important to reach out with co-creative approach to higher lever decision-makers, as examples from Hungary, Estonia or Finland indicate. Yet initiating, and especially sustaining and spreading co-creation requires shifting governance approach towards governance through conversation and learning. Co-creation certainly requires embracing learning both from failures and successes and de-learning by shifting usual ways of delivering services as well as changing our approach to risks and failures. It requires braveness from policy-makers and top managers to admit that public sector organisations may fail and have failed in the past and that to develop more adequate and effective services single organisations or service professional groups need to open up for knowledge from other actors and service beneficiaries.

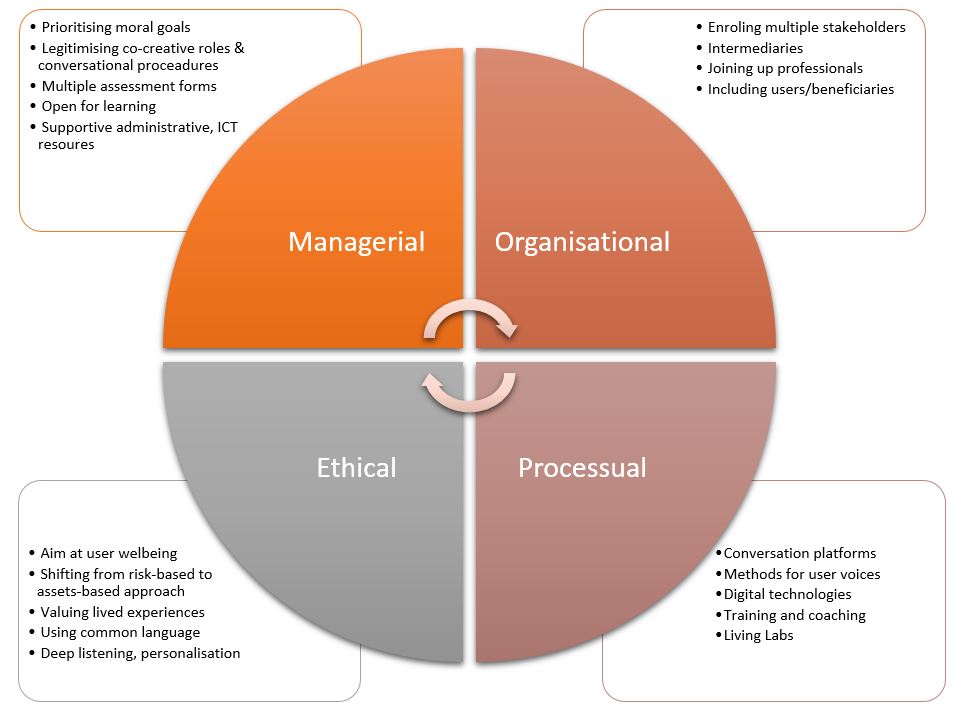

Borrowing from a typology of Tuurnas (2016) we sort out these co-creation cornerstones under 4 dimensions of governance – managerial, organizational, processual and cultural – to be considered in co-creation with so-called marginalized, vulnerable or hard to reach groups.

In sum, the right ethical compass is a key cornerstone in co-creation. It implies curiosity, strengths-based and open to trials and learning approach among professionals and managers. Co-creation also puts new demands on management and requires shifting from purely control-based to more conversational, trust-based but at the same time supportive mode of governance with extended accountability (downwards to users, side wards to peers and stakeholders and upwards to top-decision makers). It also implies managerial ability to secure access to conversational platforms, provide facilitating resources and infrastructures for sensemaking conversations and adapt roles and service assessment tools. Indeed, it requires personal efforts from all parties, consistency and time! Co-creation does imply a major shift in service culture and governance! (See more under “How to shift towards co-creative governance?”)

Establishing the above stated roles, relationships and support is a challenge, and may face resistance, not least by managers or service professionals. Yet, sustaining co-creation as an approach to service practice is often rewarding for all parties, it ensures greater social justice and service legitimacy and may even pay off economically as hearing and empowering people may focus resources on the more effective measures! (See for example results of the Spanish, Hungarian, Finish or Swedish pilots)

Please reflect in relation to your context:

How well are you prepared to engage service users and stakeholders in conversations and what would be needed? Would you need any specific platforms, intermediaries and methods to facilitate that?

What is the role of managers in your service context or service ecosystem? How may the management be better adapted to co-creative service shaping processes?

What PILOT cases inspire you most?