Julia Peck, PhD Student in Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley

Across the world, minoritized communities are pouring heart and soul into efforts to preserve, revitalize, and reclaim the use of their languages. A 2013 survey by the Endangered Languages Catalogue (ELCat) estimated that nearly half of the world’s living languages — 46%, or 3,176 languages — were endangered, meaning that their transmission to new generations has been severely interrupted. Behind these numbers lie a plethora of often-painful experiences for these languages’ users: many have borne the brunt of stigma and discrimination, or faced the pressure to assimilate that comes with many forms of nationalism; others have moved or been forced to leave their homes, and still others have seen their communities uprooted by war and genocide.

But in the past three decades, the urgency of these losses has blossomed into a global language revitalization movement with a wide range of strategies and a robust toolkit of methods. I am lucky to be working on my doctorate in one of the hubs of this movement: the UC Berkeley linguistics department, which hosts one of the largest archives of indigenous and endangered language materials in the world and the Breath of Life Institute, a biannual workshop which pairs linguists with leaders from California indigenous tribes to dive into the archives together and work on projects to revitalize their languages.

It was here at Berkeley, in a lecture for the graduate-level Indigenous Language Revitalization course, that I learned about a method I had never heard of: at-home language nesting. Joining us in class that day was Dr. Zalmai “Zeke” Zahir, a linguist and teacher of the indigenous Lushootseed language spoken in present-day Seattle, who honed in on the issue of the loss of spaces where endangered language could be spoken. After twenty years of teaching traditional-style Lushootseed classes, he lamented that he still saw his students forgetting what they had learned as soon as the class was over. Outside of the classroom, in a community with few or no living fluent speakers, where could learners go to speak?

Dr. Zahir’s solution was to draw on the idea of a “language nest” — a designated place to speak the target language, used successfully in Hawai’i (see Wilson and Kamanā 2001) and Aotearoa/New Zealand (see King 2001) to create immersion schools for children — and to show that language nests can be built in our very homes. Indeed, establishing immersion schools is not feasible in every community, but nearly everyone has control over their language use at home. An at-home language nest, therefore, is a room in the home where a learner strives to use the target language as much as possible, carving out a safe space (indeed, a nest!) for the language to live and grow (Zahir 2018).

I was astounded by the simplicity and clarity of Dr. Zahir’s idea. At the time, I was beginning my doctoral work on Ladino, the language of the Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 who scattered across the Mediterranean, bringing their 15th century Ibero-Romance varieties with them and borrowing elements of Turkish, Greek, Arabic, Serbian/Bosnian/Croatian, and French over the subsequent five centuries. Now, the vibrant Ladino revitalization movement is grappling with the challenges presented by a widely dispersed diaspora, and asking the same questions Dr. Zahir was asking: where, and how, can speakers and learners come together to speak the language? In Fredholm’s (2023) wonderful article surveying the observations and needs of Ladino teachers, one instructor voiced just this: “Me parese ke para ke la lingua tenga un avenir, tenemos ke dar espasyos ande la lingua se pueda uzar.” [I believe that for the language to have a future, we have to create spaces where the language can be used.]

One solution is the Internet, whose power Ladino language advocates have expertly wielded, especially in the wake of the 2020 pandemic and the boom of interest in Ladino classes on Zoom (see Brink-Danan 2010, Cruz Çilli 2021, Held 2010, Yebra López 2021 and 2025). But I immediately saw the beauty and strategy in carving out new spaces for Ladino in our homes: homes, after all, are where we conduct our daily lives, build habits, engage in many cultural and religious practices, feel belonging, and, for some, raise families and transmit language to them. Designating a single room as a language nest also seemed to be a brilliant way to make learning manageable for learners, who oftentimes experience overwhelm — especially when language acquisition is infused with the emotional intensity of reclaiming an endangered or ancestral language.

After putting feelers out among a few Ladino language activists and hearing their enthusiasm about the method, I got to work on an at-home language nesting kit for Ladino. I decided to start in the kitchen — so often, especially in Sephardic households, the heart of the home. I established a partnership with Nesi Altaras, a heritage Ladino speaker from Istanbul and a PhD student in History at Stanford University, and together we traveled to Istanbul, his hometown, and a hub of Ladino-speaking community and language activism. Beginning at the home of Nesi’s grandparents, we visited mother-tongue Ladino speakers across the city in their kitchens, recording them as they talked through their daily activities. One speaker made cheese sandwiches for her grandchildren as our recorders rolled, another brewed us coffee and put together his daily breakfast of bread, cheese, olives, and watermelon. How, we asked, do you say “cutting board” in Ladino? What about “peeler”? What does it sound like to have a conversation about deciding what to cook for dinner?

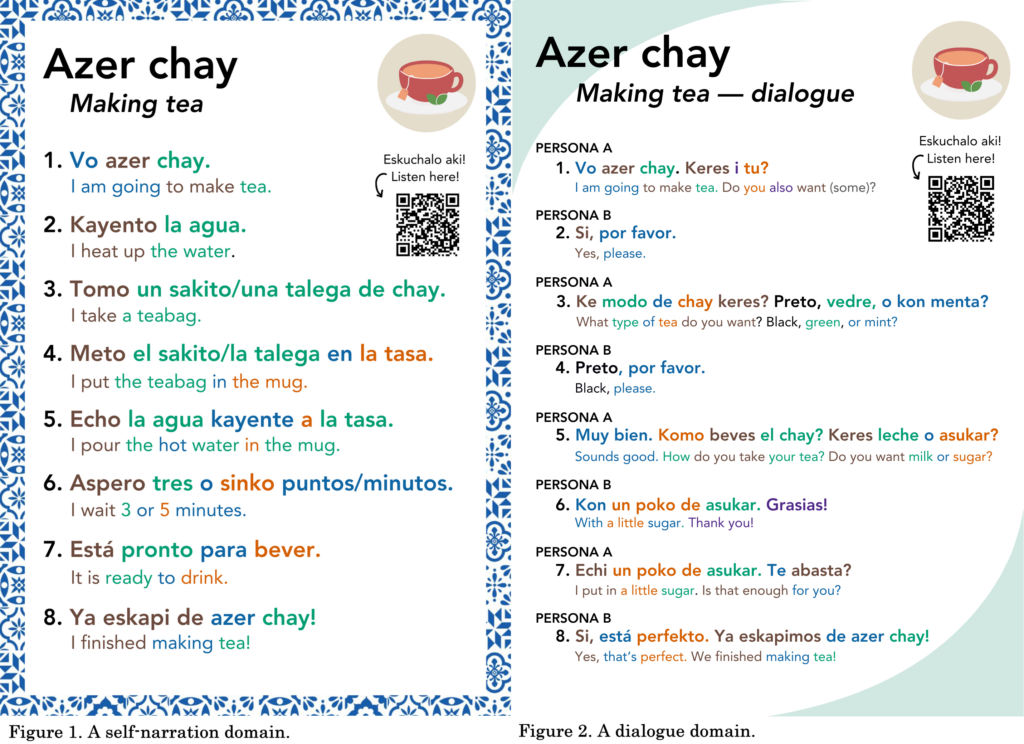

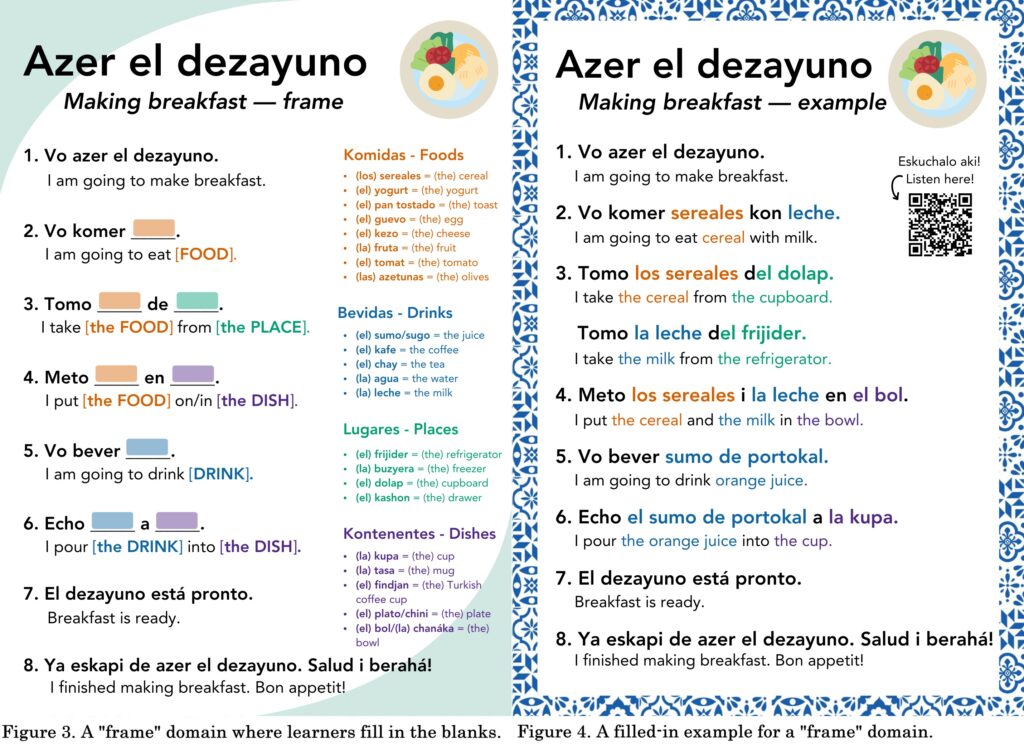

From these recordings, I developed materials for eighteen daily activities — called “domains” — that learners can use to build a language nest in their own kitchens. Many of these are self-narration tasks, where learners talk themselves through an activity in the first person, but others are dialogues and still others are “frames,” where learners are provided with the skeleton of a sentence and word banks to fill it in with. Once the text was edited by a team of speakers of various Ladino dialects, I created a 5×7 card (inches, 13x18cm) for each domain (Figures 1-4) intended to be posted visibly in a learner’s kitchen.

The cards cover a domain in 8-10 sentences, color-coded to match Ladino words with their English equivalents. They also include a QR code that links a user to our website, ladinoenkaza.com, which contains supplemental content like audio recordings and metalinguistic commentary for each domain. A learner wondering, for example, whether to say “puntos” or “minutos” (‘minutes’) as they make their tea will find on the website that “puntos” is used by most speakers in Istanbul while “minutos” is preferred by most speakers in Izmir, as well as a recording of Rachel Bortnick, a prolific Ladino language advocate, modeling the pronunciation for both.

In Spring 2024, we secured the kit’s first testers: the students of the first-ever Ladino class in the history of UC Berkeley. Each week for ten weeks, the students received a new domain for their kitchens — washing dishes, making pasta, making breakfast, and more — and they culminated the semester by writing a domain of their own. In their feedback surveys, multiple students wrote about the way that their burgeoning language nest made Ladino feel “alive” and “present” to them. At the same time, I was building a language nest in my own kitchen and shared their astonishment. After two months, as I told friends, I felt a wonderful and unmistakable presence in my kitchen, like Ladino lived there. I also noticed my proficiency skyrocketing as I now spoke the language every day.

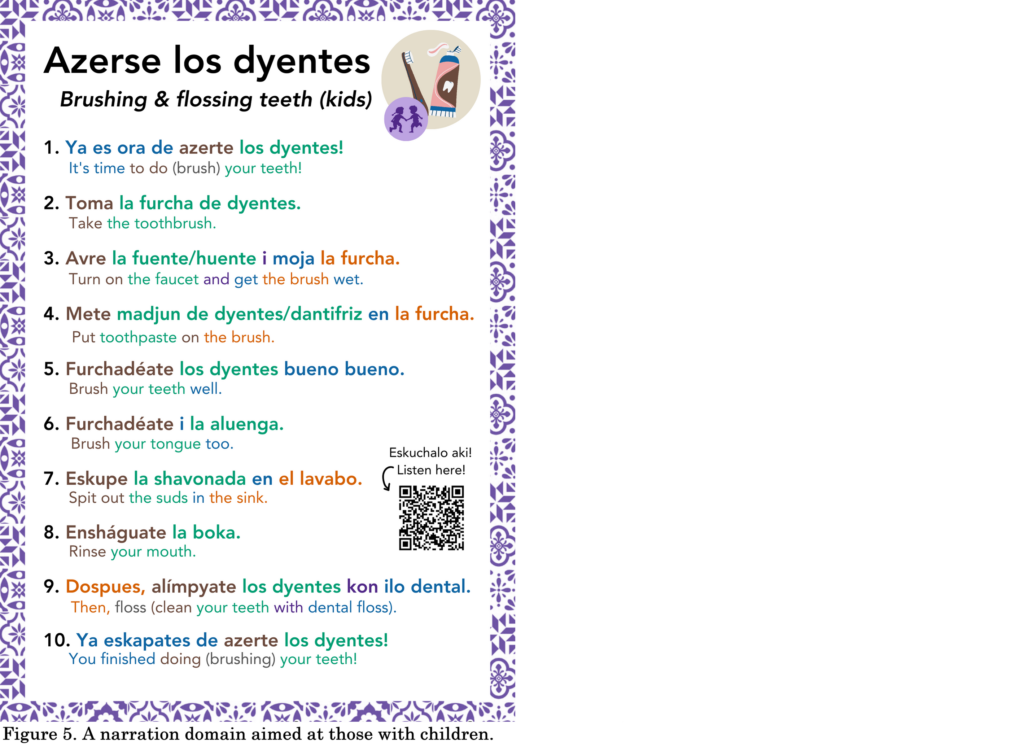

This past semester, I expanded the language nesting kit to the bathroom, thinking especially of people with young children. For them, Rachel Bortnick and I co-wrote special domains that parents or guardians can use for helping with bath time, brushing teeth, and more (Figure 5).

As we make the final touches on the Ladino language nesting resources, my team and I are looking forward to outreach. I would like to get the kit — which will come boxed, like a small board game — into the hands of as many Ladino learners as possible. To do that, we’ll be partnering with the American Ladino League and sending copies to Sephardic hubs like Seattle and Istanbul to begin with. Future iterations, ideally, will include translations of the English in the kit into Turkish and other contact languages.

But there’s another type of outreach I’ll be doing: sharing templates for language nesting with other communities and language instructors (which can currently be found on the homepage of ladinoenkaza.com). This project came to me, after all, from Dr. Zahir’s work on Lushootseed and the deep collaboration between us that followed. As we do the urgent and vital work of language revitalization, no one needs to reinvent the wheel. Instead, we need to nurture each other — just like we do in a language nest.

References

Brink-Danan, M. (2011). The Meaning of Ladino: The Semiotics of an Online Speech Community. Language & Communication, 31(2), 107–118.

Cruz Çilli, K. (2021, January 9). ‘Ladino’s Renaissance’: For This Dying Jewish Language, COVID Has Been an Unlikely Lifesaver. Kenan Cruz Çilli.

Fredholm, K. (2023). Challenges and Needs in Ladino Teaching Among Ten Language Revitalisation Activists. Meldar: Revista Internacional de Estudios Sefardíes, 4, 43–69.

Held, M. (2010). “The People Who Almost Forgot”: Judeo-Spanish Web-Based Interactions as a Digital Home-Land. El Prezente: Studies in Sephardic Culture, 4, 83–102.

King, Jeanette. “Te Kōhanga Reo: Māori Language Revitalization.” The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, edited by Leanne Hinton and Ken Hale, Academic Press, 2001, pp. 119–128.

Wilson, William, and Kauanoe Kamanā. “Mai Loko Mai O Ka ‘I‘Ini: Proceeding from a Dream. The ‘Aha Pūnana Leo Connection in Hawaiian Language Revitalization.” The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice, edited by Leanne Hinton and Ken Hale, Academic Press, 2001, pp. 147–176.

Yebra López, C. (2021). The Digital (De)territorialization of Ladino in the Twenty-First Century. WORD, 67(1), 94–116.

Yebra López, C. (2025). Ladino on the Internet: Sepharad 4. Routledge.

Zahir, Z. ʔəswəli. (2018). Language Nesting in the Home. In Leanne Hinton, Leena Huss, & Gerald Roche (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization (pp. 156–165). Routledge.